In the fall of 2000, Christopher Duran and Ashley Ellerin were outside her yellow bungalow behind Grauman's Chinese Theatre in Hollywood when a good-looking guy offered to help Duran fix his flat tire. The friendly stranger, Michael Gargiulo, paid special attention to blond beauty and part-time Las Vegas stripper Ellerin, a student at L.A.'s Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising.

Ellerin had attracted dates and boyfriends including Ashton Kutcher, then starring in That '70s Show as hunky dimwit Michael Kelso; Vin Diesel, who'd just starred in the 2000 cult hit Pitch Black; and Jeremy Sisto, later of Law & Orderfame, who reportedly flew Ellerin to a set in Toronto, where he was filming 2001's Angel Eyes.

Gargiulo, 24, an air-conditioning repairman recently arrived from Chicago, gave Duran and Ellerin his card. He lived nearby with his girlfriend in the Armor Arms on Orchid Avenue, and began visiting the bungalow where 22-year-old Ellerin lived with roommate Justin Peterson. He offered to fix their heater, and even persuaded his lover — a doctor his girlfriend Alison didn't know about — to write Ellerin a prescription for medication for her carpal tunnel syndrome.

But the cute air-conditioning guy gave some of Ellerin's friends, and her roommate, Peterson, the willies.

When Gargiulo attended a bash of young Hollywood glam types thrown by Ellerin in December, her pal Anthony Castellane later told a Los Angeles Superior Court judge, "[Gargiulo] kept his eyes on her the whole time."

Then Gargiulo began parking outside Ellerin's and Peterson's bungalow in his green Ford pickup at odd hours. When Peterson confronted him, Gargiulo insisted he was merely laying low, telling him a story that would have prompted a lot of young urbanites to cut him loose. But among this group of gorgeous go-getters, Gargiulo's dark-edged tales, which he had told to many, were met with bemusement, disdain — and continued admission to the group.

He claimed he had been linked to a murder near Chicago, that police and FBI were showing up, and that the FBI wanted to test his DNA. Peterson later told the judge Gargiulo had shown him a hunting knife strapped to his ankle. Peterson and Ellerin had heard his weird tales before, but this one freaked Peterson out. "I rushed him out of the house and told him I didn't want anything to do with his business. ... I didn't want any part of it."

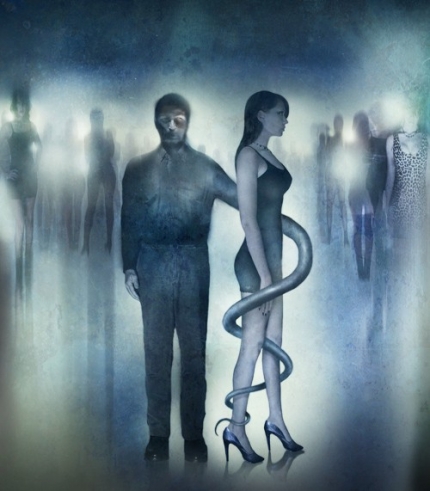

This group of beautiful young people were The Hills before anyone invented The Hills for reality TV. They were naive, living a life that college-age kids in Midwestern towns could only dream about. Sunset Boulevard. Studio parties. Clubs.

They were without a care and felt safe. So carefree, in fact, that Ellerin made love with her hunky, muscled young landlord, a Frasier bit actor, one afternoon, and casually made plans to date another dreamy boyfriend the same night — Kutcher.

But that evening, she was brutally murdered — just a few months after she pooh-poohed Peterson's warning that, beneath his too-charming surface, Gargiulo was a threat.

She "probably thought I was being dramatic about it," a sorrowful Peterson would say later. "Ashley knew I had 'an occurrence' with him and she knew how I felt. She didn't seem concerned. She was an amazing person who would make friends with everyone."

Her naïveté about the danger lurking so near tragically put Ellerin in harm's way. But the same youthful naïveté ended up protecting Kutcher, who was a biochemical-engineering student before he moved to Hollywood. His innocent outlook saved him from finding his date dead on the evening of Feb. 21, 2001. As Kutcher peered through her bungalow window, wondering why she didn't answer to his repeated knocking, the That '70s Show heartthrob mistook a trail of blood he could clearly see on her floor for spilled red wine. It was Grammy night. Mayhem never crossed the young man's mind.

Remarkably, the media largely left Kutcher alone through the pretrial hearing in June. In the decade since the tragedy that befell Ellerin, he has rarely commented on it. Kutcher went on to wed actress Demi Moore, and to star in What Happens in Vegas opposite Cameron Diaz and Killers with Katherine Heigl. He can be seen hawking Nikon's newest digital camera, and he's become a Twitter sensation, with more than a million followers.

Some of that will change at the trial, for which no date has been set, when he probably will have to testify against Gargiulo, the father of two accused of killing Ellerin and Maria Bruno, 34, who was hideously butchered 10 days after she moved into Gargiulo's gated El Monte apartment building in 2005.

Detectives found a blue surgical bootie that had been worn by Bruno's attacker outside her El Monte apartment, and theorize that the killer wore booties so he wouldn't leave forensic evidence behind. It didn't work — forensic evidence was recovered.

Gargiulo also is accused of the attempted slashing murder of heroic survivor Michelle Murphy in her Euclid Avenue apartment in Santa Monica in 2008 — the case that finally trapped the alleged sociopath.

Illinois and Los Angeles police believe Gargiulo fled the Chicago area for Hollywood after he faced too many questions in the still-unresolved 1993 murder of Tricia Pacaccio, the sister of his high school friend, in the upscale suburb of Glenview. Late last week, her father, Rick Pacaccio, slammed former and current Cook County State's attorneys Richard A. Devine and Anita Alvarez on Chicago's CBS affiliate for letting Gargiulo remain free on the streets of L.A., where he allegedly killed again after his DNA was matched to Tricia Pacaccio's remains in 2003. Although Gargiulo's DNA was found on Pacaccio's fingernails, Devine's office told Glenview police not to arrest Gargiulo, and both Devine and Alvarez have refused to prosecute him.

A spokesperson for State's Attorney Alvarez, defending her actions to CBS in Chicago last week, argued that Gargiulo's DNA could have been left during "casual" contact with Pacaccio, so they could not meet the burden of proof. Southern California authorities say Gargiulo would have been quickly charged with her murder here.

In the Los Angeles cases, Kutcher's testimony is important. It is expected to help set the time of his then-girlfriend Ellerin's slaying that harrowing evening nearly 10 years ago in the yellow bungalow behind Grauman's Chinese Theatre.

All of the alleged killer's California victims were young, gorgeous and lived near Gargiulo or in Gargiulo's own building as he moved from neighborhood to neighborhood around Southern California. A self-proclaimed forensic expert, he allegedly bragged to friends that if he were ever made to answer questions about a crime, he'd "lie, lie until you die."

Yet police say Gargiulo was tripped up by spilling his own blood — cutting himself while viciously stabbing the tiny but spirited Michelle Murphy in her bed in Santa Monica. She fought off her killer and lived to tell about it. The blood he allegedly left behind was used by Southern California detectives to link him to the Chicago and Hollywood murders.

During a 10-day hearing in June, the alleged serial killer, now gaunt and wiry, incessantly whispered and passed notes to a paralegal and his defense attorney, Charles Lindner. A parade of detectives, former friends and ex-girlfriends — including the mother of one of his two children — took the stand. On June 30, Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Michael Johnson ruled that Gargiulo would face trial.

"He was kind of a braggart and bullshit artist," says Los Angeles County Sheriff's Detective Mark Lillienfeld, who is investigating the slaying and mutilation of Bruno in El Monte five years ago.

"He told a number of people he was in the movies and was a high-end plumber for celebrities, and was friends with them," Lillienfeld says. "He would meet and befriend and associate with these women, and form a superficial relationship with them — and ultimately they would end up dead. He's every woman's nightmare."

Gargiulo grew up in Glenview, Illinois, a pretty suburb 18 miles north of Chicago, where the median household income today is $102,000. He attended Glenbrook South High School, where he played baseball. He's mostly remembered for his quick temper.

Gargiulo lived a block from the spot where 18-year-old Glenbrook South High School senior Pacaccio was found stabbed to death on her porch after she attended a school rally with friends on Aug. 14, 1993. The freakish stabbing horrified the quiet, low-crime community.

"Tricia was on the debate team, really popular, and had a scholarship to Purdue University," says LAPD homicide Detective Tom Small. "She was a well-rounded, decent girl."

Gargiulo, who was pals with Pacaccio's little brother, Doug, was questioned. He denied killing Tricia. Suburban Glenview detectives, handling what was for them an exceedingly rare murder case, interviewed dozens of people but got nowhere. Her murder eventually went into a cold-case file.

"After this happened, we didn't live in our house for four years," Pacaccio's mother, Diane Pacaccio, tells L.A. Weekly. "I can't get over it. My daughter may have been 18 years old, but she was as innocent as a child. There was no rhyme or reason why someone would do something like this to her."

The only clue to the killer's identity lay in blood and skin fragments found on Tricia Pacaccio's fingernails. But that evidence, luckily preserved by Chicago-area authorities of the early 1990s, wouldn't prove helpful for another decade, when DNA analysis finally was fully developed into a crime-fighting tool.

The Glenview cops trying to solve the murder retired. Over the years, Pacaccio's murder file bounced to different detectives, who had new theories and investigated new suspects. For a time, cops suspected Gargiulo's friend Erik — after Gargiulo implicated him. Gargiulo later recanted his statement to a grand jury.

Eventually, Gargiulo followed his brother Ken to Los Angeles, where he later was joined by his girlfriend, Alison. The couple moved to Orchid Avenue behind Grauman's Chinese Theatre in Hollywood, not far from Ellerin's bungalow.

They seemed to live the classic Midwestern kids' dream, with Gargiulo even getting a job as a doorman at the Rainbow Bar & Grill on the Sunset Strip in 1999. But his bad temper got him fired — for decking a patron.

By the fall of 2000, Gargiulo was an air-conditioning repairman. Investigators say his creepy side, by this time, had begun asserting itself: While living with his Illinois girlfriend he was secretly dating a McDonald's cashier, Velma Carrillo, whom he met in an AOL chat room. He told her one of his many phony personal histories, bragging that he'd studied forensics and came to California to train as an Olympic boxer.

There were small kernels of truth in his many fake tales. "In fact, his brother was more of the boxer," LAPD Detective Small says. "Mike had it in his mind he was a boxer, but I don't think he had any real bouts. His brother got ... inspired to be a professional. Mike, being a copycat, was telling people he was a boxer."

He even told Carrillo, with whom he lived periodically, that he'd left Illinois because of a murder he didn't commit.

"He said he knew who did that murder," says Los Angeles County Sheriff's Detective Joseph Purcell. "He couldn't say who that person was. And he also mentioned his DNA would be present at the murder scene, because the victim was almost family to him and he was always at the location."

In Los Angeles, Gargiulo parlayed his story of fleeing from a dark Chicago past into a selling point of sorts.

Says Small, "I was always amazed that he was really free with that, reciting almost the same thing to people. I don't know if he was trying to create a rise in people, or scare them."

He was convincing, as experts say many sociopaths are. Carrillo had a child with him. And authorities believe this secret second life with Carrillo unfolded without the apparent knowledge of yet another secret girlfriend, who was a doctor, or his ongoing original girlfriend from Chicago, Alison.

When he met roommates Ellerin and Peterson that day 10 years ago near their bungalow, Gargiulo mixed together elements of his phony tales. He told them he was a professional boxer but had been electrocuted fixing an air-conditioning unit. All lies, police say.

He eventually told Ellerin and Peterson his strange story of being hounded by police over an unsolved murder of an "ex-girlfriend" in Chicago. But they were young, upwardly mobile people out to make it in Hollywood. They were dashing off to hot parties, hanging with famous people and having the time of their lives. Justin Peterson did sound the alarm. But Ellerin and others ignored Gargiulo's weird mutterings.

The morning of Feb. 21, 2001, started on the upswing. Ellerin and her father, visiting from the wealthy Bay Area suburb of Los Altos, were doing some remodeling and painting at her place. Later that day the Grammys would be on, and she spoke twice with Kutcher, whom she'd begun casually dating, making plans to meet him for drinks.

Ellerin dropped off her father at the airport in the afternoon and called her handsome landlord, Mark Durbin, who had bit parts on Frasier and, later, Six Feet Under and No Ordinary Family. He agreed to fix her ceiling fan and move some furniture.

The lean, muscular Durbin testified in June that he and Ellerin were involved in a "blossoming" relationship. He stopped by at around 7 p.m. and the two made love. Ellerin was playing the field, having recently broken up with her acting-coach boyfriend.

"She had tons of boyfriends," Detective Small says. "At that time Kutcher was still coming up. He hadn't established his big-time credentials yet. They met through a mutual friend. It was a friendly thing. They went out a couple of times."

A few minutes after Durbin left, Ellerin called Kutcher to ask him if she should come to his friend Kristy's to watch the Grammys. No, he told her, he would meet her at her bungalow later.

Kutcher, interviewed by detectives the day after Ellerin's slaying, said he called her twice that night but she didn't answer. He blamed bad reception and drove over at 10:45 p.m. Ellerin's lights were on and her maroon BMW was in the drive. He knocked several times, and when she didn't answer he peered through a front window.

Kutcher saw what he assumed to be red wine stains leading toward the bedroom. "He figured she was upset" because he was late, and "she brushed him off. So he left," testified LAPD Detective Thomas Shevolek.

It was a fortuitous error by the young actor, although he might not say so were he to comment on the terrible end that befell his beautiful date that night.

Had Kutcher discovered her gruesomely slashed body — sprawled in a hallway near the bathroom just out of his view — there is no way to know what would have become of the buoyant young man's life and career in the years to follow.

But Kutcher sensed nothing amiss. He got in his car and drove away.

Ellerin's body was found by a roommate the next morning. She had been stabbed 35 times. Amidst the carnage, it was clear she had been preparing for her evening out with Kutcher. Her curling iron was found nearby. Her blow-dryer was on the toilet seat. Detective Small can't shake the memories. "I still smell it," he says. "The whole crime scene is vivid in my head."

Clues as to what had happened include the fact that her doors were locked and her windows had bars. "Probably someone came to the door," Small says, "and the rest is history. She knew the guy, and according to the people who knew her, if she knew you, she would let you in."

Small sums up the alleged killer this way: "Gargiulo is all about himself. I think he thought of himself as a major player. A tough guy. He has proven he is as dangerous as hell. He is not the guy you would want to bring home to dinner."

Small and his partner ruled out many suspects, but they were hampered by the lack of DNA evidence. Small heard about "Mike the furnace man," but none of Ellerin's friends knew his last name. Detectives learned that "Mike" had told people a story about being hit by a cement truck when developers were building the Kodak Theatre at Hollywood & Highland. "Mike" boasted the accident was going to make him rich because he'd filed a lawsuit.

But when Small contacted the construction company and lawyers for the Kodak, there was no such accident — and neither entity was being sued.

So Small searched all traffic accidents near the Kodak. He unearthed one in which a dog was struck by a car at Orchid and Franklin avenues. The dog's owner had insisted on filing an accident report.

The owner of the vehicle that struck the dog? Michael Gargiulo.

Detective Small showed Gargiulo's DMV driver's license photo to Ellerin's friends in the fall of 2002. "It really had some promise, and I got to know more and more about him — and found people who had contact with him," Small recalls. "I was open-minded. I didn't know who my killer was at the time."

Then, out of the blue a few days later, Small's partner got a call from Cook County, Illinois, cold-case Detective Lou Sala, who had taken over the Tricia Pacaccio investigation. Sala was collecting DNA from everyone the original detectives had interviewed in the pre-DNA days to again rule them out as suspects.

In a remarkable coincidence, Sala and his partner were in L.A. to DNA-swab Gargiulo. Sala was on the phone, seeking the LAPD's help to track down Gargiulo's location. Gargiulo was tough to find, in part, police later learned, because he never put utilities or leases in his own name.

Small says, of getting a phone call from Illinois police seeking the same man for a different killing: "My partner said the name and looked at me — and my jaw was on the floor."

Small had only just run across the name Michael Gargiulo in the dog-hitting accident. "I said, 'Get them over here!' I was on cloud nine. I didn't want to retire until this one was closed. I showed [Sala] and his partner the [DMV] picture, and they said, 'How do you know him?' That is how the whole thing went down."

The two teams of detectives, from Los Angeles and Glenview, compared the way two female knifing victims separated by substantial time and distance — Ashley Ellerin and Tricia Pacaccio — had been stabbed. Small says: "The similarities were phenomenal."

Small soon tracked down Gargiulo, by then living in West Los Angeles with a new girlfriend. Her name, not Gargiulo's, was on the lease of their Clarke Drive apartment.

In December 2002, detectives obtained a blood sample from Gargiulo. Police say the furious Gargiulo tried to fight off authorities. It would take months before the sample was matched to blood that had been found on Pacaccio's nails.

While that slow process unfolded, in February 2003, Gargiulo began a short-lived relationship with Maria Gurrola, the former wife of a famous Mexican singer who had hired Gargiulo to fix her air-conditioning unit. She told detectives Gargiulo wore blue surgical shoe covers and followed her around her house until she agreed to go on a date with him.

After they began dating, he moved into her Lakewood home with her and her four children. But things quickly soured when he allegedly punched her and asked her for a loan. She filed a restraining order, alleging that he was stalking her. She said he'd threatened to kill her and bragged he'd get away with it because of his "extensive knowledge" of forensics.

In September 2003, 10 months after detectives took a blood sample from Gargiulo, the human DNA found on the fingernails of Illinois high schooler Pacaccio in 1993 was matched to Gargiulo.

Police had their man, detectives say, and two women were dead.

But in a screwup of tragic proportions, Cook County prosecutors declined to file charges against Gargiulo. In a still-unexplained decision, Illinois authorities told the Pacaccio family the evidence was not strong enough — despite the DNA match between the person who slaughtered high schooler Pacaccio near Chicago and the air-conditioning repairman obsessed with women like Ashton Kutcher's girlfriend.

The Cook County prosecutor's office refuses to explain to the Weekly the reasons for its unusual decision, or any other matters involving the Pacaccio murder investigation, which remains open and officially unsolved.

The Cook County State's Attorney's Office during the time of those decisions was run by a powerful politician, State's Attorney Richard A. Devine, who held tight control over his office. Devine's special prosecutor, Scott Cassidy, told police not to arrest Gargiulo, dismissing the DNA match by insisting Gargiulo could have left his DNA on Pacaccio innocently. Cassidy did not respond to the Weekly's attempts to reach him. But many witnesses told police that Pacaccio hugged and touched friends and her boyfriend on the day she died, yet did not see Michael Gargiulo — yet only his blood DNA was on her fingernails.

LAPD's Small called the state's attorney's choice a "bunch of shenanigans."

Pacaccio's mother, Diane, tells the Weekly, "I don't know why they didn't arrest him. They claimed there wasn't enough evidence. I said, 'Who else's DNA was on her?' For some reason they must have a low opinion of [a jury] here [in Chicago]. Who wouldn't convict someone from DNA?"

Small says the LAPD's hands were tied. It couldn't arrest Gargiulo because the LAPD found no human trace evidence left by the killer at the Ellerin crime scene, and it can't arrest someone on the basis of evidence in another region — such as the blood DNA found on Pacaccio's fingernails in Glenview.

The LAPD could only pray that Devine would file charges. Instead, the state's attorney retired to teach law.

"[The Cook County detectives] actually went back over this stuff and did everything they could," Small says. "It was the State's Attorney's Office that is not filing. ... I am not privy to everything in their investigation. In totality of the circumstances and physical evidence out here, we would prosecute it. Frankly, I think it is a bunch of shenanigans, but it is not my say."

Devine, who was elected by voters to three terms as state's attorney from 1996 to 2008, now teaches law at Loyola University Chicago School of Law. His elected successor, Anita Alvarez, has similarly declined to prosecute Gargiulo.

"It is [the State's Attorney's Office] who have to answer to the Pacaccios on why they aren't moving on it," Small says. And not just to the Pacaccios. To all of Gargiulo's other alleged victims, and their families and friends.

Left free in California in late 2003 by Illinois prosecutors, Gargiulo continued dating other unsuspecting Southern California women. One was Grace Kwak, whom he met on Match.com.

By September 2005, he was living with Kwak in a second-floor gated apartment in the 4600 block of Arden Way in El Monte, east of Los Angeles. Kwak was pregnant, and Gargiulo launched a new air-conditioning business called 24 Hour Heating & Air.

Like Gargiulo's other relationships, this one went bad fast. Sick of being beaten, Kwak has testified, she moved out on Thanksgiving weekend in 2005. Within days, 32-year-old Maria Bruno, a stunning and shapely mother of four, moved into a unit on the first floor of the Arden Way building.

An El Salvadoran immigrant, Bruno was dating a manager at Barcelona restaurant in Pasadena and worked as the clerk for the collections department at Leader's Furniture in El Monte.

"She worked one day with me," recalls Leader's Furniture owner George Liberman. "We knew her because she came to buy some furniture and applied for a job. I really never hire customers, but she was very different. She was pretty, nice and had a good temperament."

On Dec. 1, 10 days after she moved into the Arden Way apartment, Bruno was discovered with her throat slashed and her chest mutilated, with one breast cut from her body. Outside her apartment, police found a blue surgical bootie.

A neighbor, Robert Rasmussen, told police that days before, a man wearing a hoodie and baseball hat was jiggling Bruno's doorknob and peering through her window. Another day, Rasmussen says, he saw the man following her as she carried groceries. Police believe it was Gargiulo.

"She went into the apartment and he followed her in," Rasmussen says. "The minute he stepped over the threshold, he backed out and the door was shut" in his face.

During the preliminary hearing in L.A. last summer, Detective Lillienfeld told the judge the Bruno murder scene was so chilling that he still remembers what day of the week it was — a Thursday. Lillienfeld remembers spotting the blue surgical shoe cover in front of Bruno's apartment. A screen had been pried loose from her kitchen window.

Detectives interviewed neighbors and checked arrest records of the building's occupants. Nobody in the gated community seemed capable of such carnage.

"We ran the criminal history and nobody appeared to have a serious arrest record," Lillienfeld says.

Gargiulo was never home when police knocked and never responded to cards police left. He was never interviewed, and Bruno's murder remained unsolved.

By 2008, Gargiulo had married and moved to Santa Monica. He'd met his wife at a showroom for plumbing and bathroom remodeling. The couple lived with her mother in the 1200 block of Euclid Avenue.

On April 28, Michelle Murphy, a neighbor who lived across the alley in a second-floor apartment, was awakened by "someone on top of me ... stabbing me," she has testified. The attacker, who crept in through a window, was wearing a hoodie and baseball cap. He stabbed her repeatedly.

Miraculously, the 5-foot-1-inch Murphy managed to kick and fight him off. He fell and fled — and this time, local detectives caught a break: Her attacker had cut himself during Murphy's heroic struggle.

Santa Monica Police Department Sergeant Rich Lewis ordered the attacker's spilled blood tested for DNA matches in police databases, and hit pay dirt a month later. The blood was matched to Gargiulo, whose DNA had been swabbed years earlier by detectives investigating him for the murders of Pacaccio and Ellerin.

Gargiulo lived in a second-floor apartment diagonally across the alley from Murphy, which afforded him a bird's-eye view of her place. Murphy testified that before the attack, Gargiulo passed her in the alley while she was working out and tried to talk to her.

When Sgt. Lewis saw that Gargiulo's DNA was left at the scenes of the attacks on both Murphy and Pacaccio, he remembered a conversation he'd had months earlier with Los Angeles County Sheriff's Detective Lillienfeld. Lillienfeld had told Lewis about the unsolved slaying and mutilation of Maria Bruno in El Monte.

The violent knifing Murphy had survived seemed eerily similar to the Bruno tragedy. Could it be the same assailant?

He called Lillienfeld and his hunch paid off. Lewis says, "It was like the lottery. It is ironic, but it does happen. When officers network, we solve cases."

Gargiulo was arrested on June 6, 2008, by the Santa Monica Police Department and charged with the attempted murder of Michelle Murphy. He was later charged with the murders of Ellerin and Bruno.

Diane Pacaccio has pure contempt for the Cook County state's attorneys, who have failed to act, even though the human detritus found on her dead daughter's fingernails has been linked via DNA tests to Gargiulo.

"Their job was handed to them when they found out it was his DNA," she says. "After years it was finally handed to them, and they didn't do anything about it. They should be ashamed of themselves. There was no way in high hell that the DNA should have been on my daughter."

Reflecting on all that has happened, Diane Pacaccio says, "I don't know why [the State's Attorney's Office] didn't put him in jail. ... I just don't understand it." Even now, so many years after losing her daughter, "I can barely leave the house. I can't get over it. I don't want them to think they are leaving my daughter's case as an open case."

For this mother, the case that will one day unfold in a Los Angeles courtroom 2,000 miles from Cook County is already closed. "If it wasn't for Tricia, he wouldn't be in jail today," Pacaccio says.

Of those who died after Gargiulo slipped in among the beautiful young people of Los Angeles 10 years ago, she can only say, "These girls could have been alive."