Almost two decades later Niki Lopez still has nightmares. She remembers her child hood in the United Nuwaubian Nation of Moors and the way she and the other young followers were beaten with wire hangers, belts and brooms by cult members. The way she was groomed to be a sex slave for the group’s charismatic leader, Dwight “Malachi” York, and the way York began raping her when shewasjust15.“Weweren’tjustsexuallyabused, we were emotionally and physically abused,” says Lopez, now a 43-year-old artist and single mother ofa9-year-oldsonandlivinginFortLauderdale. “I was cut off from society. I had no one to advocate for me.”

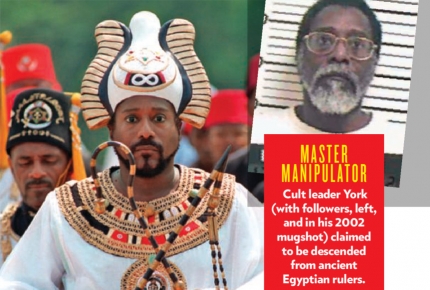

Not only did Lopez become her own powerful advocate, but she helped save dozens of others too. In 2000, at the age of 25, she found the courage to leave—and revealed to law enforcement the atrocities taking place behind the gates of the cult’s Egyptian-inspired compound in Eatonton, Ga. After she told her story to the FBI, dozens of other victims came forward to give investigators additional details of sexual and physical abuse in the group, leading to a federal raid on the compound, known as Tama-Re, in May 2002. York was arrested and charged with multiple state and federal crimes, including more than 100 counts of child molestation, six counts of transporting minors across state lines for sexual purposes and ï¬ve counts of racketeering. “It was horriï¬c,” says cult expert Rick Ross. “York saw himself as a channel between God and the world. He was a master manipulator.”

Convicted in 2004, York was sentenced to 135 years in federal prison, where the 73-year-old remains. But Lopez is determined to keep the story of what happened to her inside the cult alive in hopes that it can help save others. “I know how much of this abuse relies on silence and secrecy,” she says. “I’m going to talk about it because he was expecting me to be silent.”

Lopez was just 11 when her mother joined York’s Brooklyn compound in 1986, attracted to the cult’s teachings of black supremacy and Islamic mysticism. “I just thought of him as this magical being,” says Lopez. “I was taught he was a man of miracles and everyone had to be loyal to him.”

In 1993 Lopez and her mother were among the estimated 300 members who followed York to rural Georgia, where he bought a 476-acre plot of land and began building the Tama-Re complex, with 40-ft. pyramids and a giant Sphinx sculpture, a tribute, he said, to their ancient Egyptian ancestors. Lopez says she was 12 when York’s sexual grooming began. Initially he allowed her and a few other children special access to his house to watch cartoons and eat junk food. Soon, she says, he introduced her to pornography, and she was taught how to perform oral sex by one of York’s wives, who convinced her that sex with York was a Sudanese tradition to prepare her for marriage. One night Lopez says she was asked to stay behind at York’s house, where he held her down and raped her. “I was told it was a good thing to be chosen,” she says.

‘IT’S STILL A STRUGGLE, BUT TRYING TO HELP OTHERS BY SPEAKING OUT HELPS ME’

—SURVIVOR NIKI LOPEZ

But over the years Lopez grew depressed and suicidal, and as York began to molest increasingly younger boys and girls, she knew she had to leave. She eventually tracked down her biological father in Atlanta, and he encouraged her to report York’s abuse. Testifying as one of the prosecution’s star witnesses at York’s trial, “I felt empowered,” she says. “I lived my whole life being told what to do by this person, and he governed everything that I did.”

That sense of self-empowerment is one that Lopez holds onto, even while she struggles with PTSD and anxiety. Although the cult mainly collapsed after York’s arrest, some of his loyal followers still send her hate messages. And her relationship with her mother, who she says didn’t know about the abuse at the time, remains fractured. But the self-employed visual artist and graphic designer says she copes through art and activism aimed at helping other abuse survivors. “It’s cathartic for me,” she says. “It’s giving people permission tosharewhathappenedtothemandtohealalong with them.”

Download PDF Version

Download PDF Version